I'm doing consciously more than needed - our next reading session is about ethics, and I'd rather take some time to express my thoughts explicitly than to keep them creeping fuzzily around in the back of my mind.

1. WC states (Teachers) “are not justified in intruding into (pupils’) emotions, their thoughts, their feelings, their beliefs, their attitudes.” FM says that "Unduly excited fear reflexes, uncontrolled emotions, prejudices and fixed habits, are retarding factors in all human development. They need our serious attention, for they are linked up with all psycho-physical processes employed in growth and development on the subconscious plane." (CCCI – Chapter 6)

Presumably for a person to change their habit of use these factors FM enumerates have to be change. Do you think it is possible to help people change their pattern of use without dealing with people’s emotions, thoughts, feelings and beliefs?

I don't think it's possible to change a person's pattern of use without dealing with emotions, thoughts, feelings and beliefs. Former factors are an integral part of a person's self. Assuming that an AT teacher could help a pupil to change his/her use of the self without dealing with these factors neglects Alexander's core idea of psycho-physical unity.

The key word in WC's statement is in my point of view 'intrude'. A teacher does not intrude a student's body (like maybe physio's or chiropractors do), so a similar 'soft' and 'guiding' approach is required to deal with thoughts, beliefs, attitudes and emotions.

Psychological studies have shown that changes in attitude hardly change behaviour, but changed behaviour affects attitudes. An AT teacher can create the space to explore different ways to behave (act, do), which in turn changes attitudes, beliefs, etc.

2. If the answer is “no” how might we give these “our serious attention” in a way that doesn’t take us out of our range of what we are trained to do as AT teachers?

Basically, an AT teacher should deal with 'mental' pattern in a similar way to physical patterns, by the use of indirect procedures. We would not treat a broken bone with AT, and severe emotional problems belong to a similar category. When making pupils aware of bad use in thinking, we need the same sensitivity we apply with our hands.

3. If the answer is “yes” then what is the process we take people who suffer from these “retarding factors” through to help them to change their use?

Giving pupils new experiences, having a consistent way of teaching the principles of AT and avoiding 'emotional triggers' are essential to help the pupil to gain more freedom.

4. What does Walter suggest and what are your thoughts?

I would summarize Walter's suggestion about ethics to three major points:

1) Mind you own business

2) Teach the technique as hands-on as possible

3) Don't hesitate redirecting pupils to other sources of help, know your competencies

This doesn't prevent you as teacher from providing just what a student needs to release 'mental holding patterns', albeit with indirect procedures. This can be best achieved in a cooperative, subtle manner, confrontation is counterproductive in most but rare cases.

5. In regard to “unduly excited fear reflexes, uncontrolled emotions, prejudices and fixed habits” and “individual errors and delusions” how does FM propose that we approach these “retarding factors”?

FM suggest to rebuild confidence in the pupil by liberating him/her from the idea of doing this 'correctly', and providing sucessful experiences of deploying satisfactory means-whereby. It is also necessary to improve the reliability of sensory appreciation. The student then has to apply the AT principles generally, and not only for specific situations.

6. If you can accept that some types of beliefs are harmful to a persons use and others not harmful pick an example of a harmful and a non-harmful belief.

Harmful believe: There's a quick fix for everything.

Non-harmful believe: There's more between heaven and earth than science can tell us.

7. If a pupil is undertaking a procedure, treatment or doing exercises, which are clearly impacting badly on their use, what is a teacher’s responsibility? If you decide that it is appropriate for a teacher to give advice in such a case how could this be done?

The advice should be given in a careful manner, by making the student aware of the bad impact of his choice.

Wednesday, May 27

Monday, May 25

Toying with tensegrity - part 2

Please start with first part, in case you missed it.

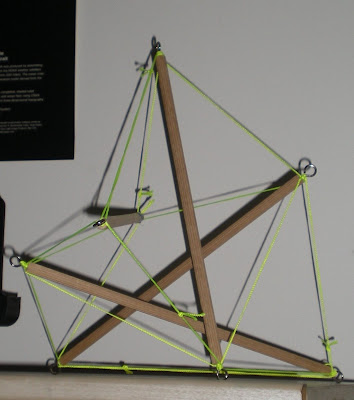

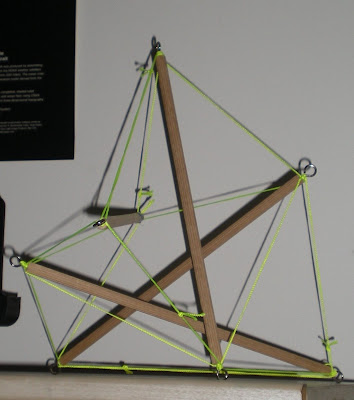

Even though photos cannot capture the dynamics of a tensegrity model, they simply help illustrating why I got hooked on tensegrity. I managed to find a shot of the very first tensegrity tower I build, using nylon string for all cords. You can see some slack triangles, but the structure proved rigid and balanced enough to hold a juggling ball.

The limited stretch of nylon produces very rigid structures, and tuning can be quite tedious. However, when the cords have good prefabricated length, these models can easily used in groups to explore its dynamics.

The tower itself looked quite different from the model shown with the instructions, the tensuls kept their shapes instead have being shaped by the different loads on the tension elements.

Without elastic cord my tower had interesting qualities, but not the aesthetic appeal and surprising dynamic I expected. I decided to construct a 4 strut tensegrity structure next, which started an amazing learning experience. I estimated the cord length by using figure from a Java applet, and prepared what I needed. I didn't have any visual instruction how to lay out and construct this model, so I just started off, triangulated around and attached cords.

I marked the dowels so I could distiguish them, and had a way to write out the needed connections. The 4 strut model has 4 triangles and two 'diagonals'. On my first attempt to attach the second diagonal, while the model popped into three dimensions, some cord slipped off and the model collapsed into a chaos of rods and strings.

It took me roughly a day to figure out decent length for the final tension cords, and how to lay out the struts to allow them to unfold. I didn't count the amount of times I assembled and disassembled the flurry of strings and dowels, and how often I repeated the same mistakes in the process. Perseverance paid out, and I had a new structure to explore. I won't take it apart too soon, though, I'm still not too confident about rebuilding it again.

I used 30 cm length (instead of 20cm) for the 4 strut model, and used the left over struts for easy task: A simple 3 strut tensul with the same cord length for the main triangles. I had some elastic cord now (still not the right thing), yet combined nylon and stretch cord for the model. The final model appear much taller than the elements of my first tower. I placed the model next to it, and noticed that by adding 50% length to the compression element I gained twice the height.

Finally I found the material suggested for these kind models: Plastic stretch cord used for beading. Well, currently I'm waiting for a delivery of enough supply for extended experimentation. I picked up a similar material in a craft shop, unfortunately with just 0.5 mm diameter. It works okay so far, although the stretch factor does not work as expected yet.

The material makes it difficult to tune the models, and fix the cords to their attachment points. I managed to get three levels together, but the stabilizing triangles permanently flattened the lowest level. I guess I'll take more time for tuning the single tensuls, and fixings the cords more to the attachment.

I fiddled for a while with more securing triangles, and ended up with some entangled cord on one strut. Instead of trying any more to stand the model up, I took two more cords and hung the model up.

Depending on the lighting, the transparent tension cords are virtually invisible, enhancing the floatiness of the model. It reminds me of the idea of being 'skyhooked'. Funny enough, you can move lower parts of the model around without affecting the 'head', but when the head moves, the body follows...

I still have a long way to go if want to skeletal structures as tensegrity models. I wouldn't mind coming across enough model to buy them. Experiencing tensegrity helped me a lot understanding the process I started with learning the Alexander Technique.

Tuning one part of a tensegrity structure affect the tension levels throughout the entire structure. When we release a habitual holding pattern, other tensors (muscles) have to become active. A tensegrity model balances by specific patterns of pretension, more overall tension yields more rigidity. Sounds familiar?

By doing less we retune the tension elements, or rather, develop new patterns of feedback with our muscle spindles. We need to change our habitual reaction to this muscle spindle feedback, inhibiting the impulse to 'hold on' and send our head forward instead. This sounds easy, but many obstacles lurk on that path.

Depending on how one has used him/herself the tensors responsible for balance have weakened. Using them can 'feel wrong', and can cause discomfort and pain. We might not be aware that changes affect more than one area, or underestimate the importance of primary control.

Seeing, building and touching the floating elements of a tensegrity structure changed my conception of my own bones from the semi-solid stack of columns to mere floating compression elements. And I hope it will help my future student's understanding.

Even though photos cannot capture the dynamics of a tensegrity model, they simply help illustrating why I got hooked on tensegrity. I managed to find a shot of the very first tensegrity tower I build, using nylon string for all cords. You can see some slack triangles, but the structure proved rigid and balanced enough to hold a juggling ball.

The limited stretch of nylon produces very rigid structures, and tuning can be quite tedious. However, when the cords have good prefabricated length, these models can easily used in groups to explore its dynamics.

The tower itself looked quite different from the model shown with the instructions, the tensuls kept their shapes instead have being shaped by the different loads on the tension elements.

Without elastic cord my tower had interesting qualities, but not the aesthetic appeal and surprising dynamic I expected. I decided to construct a 4 strut tensegrity structure next, which started an amazing learning experience. I estimated the cord length by using figure from a Java applet, and prepared what I needed. I didn't have any visual instruction how to lay out and construct this model, so I just started off, triangulated around and attached cords.

I marked the dowels so I could distiguish them, and had a way to write out the needed connections. The 4 strut model has 4 triangles and two 'diagonals'. On my first attempt to attach the second diagonal, while the model popped into three dimensions, some cord slipped off and the model collapsed into a chaos of rods and strings.

It took me roughly a day to figure out decent length for the final tension cords, and how to lay out the struts to allow them to unfold. I didn't count the amount of times I assembled and disassembled the flurry of strings and dowels, and how often I repeated the same mistakes in the process. Perseverance paid out, and I had a new structure to explore. I won't take it apart too soon, though, I'm still not too confident about rebuilding it again.

I used 30 cm length (instead of 20cm) for the 4 strut model, and used the left over struts for easy task: A simple 3 strut tensul with the same cord length for the main triangles. I had some elastic cord now (still not the right thing), yet combined nylon and stretch cord for the model. The final model appear much taller than the elements of my first tower. I placed the model next to it, and noticed that by adding 50% length to the compression element I gained twice the height.

Finally I found the material suggested for these kind models: Plastic stretch cord used for beading. Well, currently I'm waiting for a delivery of enough supply for extended experimentation. I picked up a similar material in a craft shop, unfortunately with just 0.5 mm diameter. It works okay so far, although the stretch factor does not work as expected yet.

The material makes it difficult to tune the models, and fix the cords to their attachment points. I managed to get three levels together, but the stabilizing triangles permanently flattened the lowest level. I guess I'll take more time for tuning the single tensuls, and fixings the cords more to the attachment.

I fiddled for a while with more securing triangles, and ended up with some entangled cord on one strut. Instead of trying any more to stand the model up, I took two more cords and hung the model up.

Depending on the lighting, the transparent tension cords are virtually invisible, enhancing the floatiness of the model. It reminds me of the idea of being 'skyhooked'. Funny enough, you can move lower parts of the model around without affecting the 'head', but when the head moves, the body follows...

I still have a long way to go if want to skeletal structures as tensegrity models. I wouldn't mind coming across enough model to buy them. Experiencing tensegrity helped me a lot understanding the process I started with learning the Alexander Technique.

Tuning one part of a tensegrity structure affect the tension levels throughout the entire structure. When we release a habitual holding pattern, other tensors (muscles) have to become active. A tensegrity model balances by specific patterns of pretension, more overall tension yields more rigidity. Sounds familiar?

By doing less we retune the tension elements, or rather, develop new patterns of feedback with our muscle spindles. We need to change our habitual reaction to this muscle spindle feedback, inhibiting the impulse to 'hold on' and send our head forward instead. This sounds easy, but many obstacles lurk on that path.

Depending on how one has used him/herself the tensors responsible for balance have weakened. Using them can 'feel wrong', and can cause discomfort and pain. We might not be aware that changes affect more than one area, or underestimate the importance of primary control.

Seeing, building and touching the floating elements of a tensegrity structure changed my conception of my own bones from the semi-solid stack of columns to mere floating compression elements. And I hope it will help my future student's understanding.

Labels:

inhibition,

primary control,

tensegrity,

tensul,

use

Thursday, May 21

Toying with tensegrity

About half a year of weekly Alexander Technique lessons I doubted a bit about their use. My teacher told me that our body works as a tensegrity system, and I got hooked again. Even more, I decided to get on a teacher training myself - finally I could integrate Buckminster Fuller's ideas actively into what I want to do for a living.

The notion of tensegrity reappeared lately during our anatomy sessions, and I realised that most people seemed to have no idea about tensegrity. I had yet to learn that conceptual knowledge has to be embodied for a full understanding.

I had seen a good instruction for building a tensegrity table, and I wanted to give a shot myself. I decided to start with a proof of concept, using PVC instead of copper, trying to translate the imperial measures into metric, adapting a bit for the conversion.

The first prototype didn't work well, the cord length of the main triangles of the tensules was too long. The second prototype taught me about the importance of prestress for the connecting diagonals, and dampened my hope a bit to soon have a nice self-made coffee table.

So I researched the web a bit to stumble across the building instructions for a tensegrity tower made of wooden dowels and plastic cords, and the next visit in the hardware store was due. I don't consider myself a handy man, but I usually don't shy away from manual tasks. Sawing a dowel, drilling some holes and knotting some strings appeared easy preparations to gain some insights to the dynamics of tensegrity structures.

Working on this model allowed me to work on myself as well - I had no time constraints, no boss, no obligation to finish the project, nothing but my curiosity that motivated me. I felt quite proud after cutting the dowel into twelve pieces of similar lengths (2mm tolerance on 20 cm). surprised about the difficulty finding an easy way to drill the holes and about my patience following the instructions step by step. I prepared everything for four tensuls, again translating from imperial to metric measures and improvising with the chocie of materials.

I didn't find stretchy plastic cord, and used nylon string instead. When I tried to assemble the first tensule, the nylon cords wasn't stretchy enough to put the model together. I realised some frustration about preparing more than 30 pieces of string I couldn't use, but decided to make some bigger loops, this time only enough more one model.

I started off with main triangles, and thought about reusing some of the loops already prepared to see how it works out. The first structure that emerged rigid still looked very crooked, I used different length for the connecting diagonals. But I had entered the third dimension, and now wanted to find out a decent length for this 3d puzzle. I unhooked one diagonal, and due to the tension and flopped over from rigid box shape to a messy bunch of rods and strings. Wow.

I found a good length experimentally and prepared the next set of loops for the remaining tensuls. Fixing the orientation of the rods with rubber strings made the assembly easy and fast, and I had four tensuls ready to be piled on top of each other.

The nylon string didn't stretch easily, and I needed some force to threat the first two tensuls together. Although the lower triangle of the upper tensul hung around without tension, the combined tensuls showed increased rigidity.

Finally, I could tune my first tensegrity tower to balance it out. Stunned by the weird thing I build, I took some photos - unfortunately too blurred to be usable. However, as a picture cannot really capture the surprising qualities of a tensegrity model (unless explicitly designed for artistic purpose), I didn't regret capturing this historic moment for me with a crystal clear digital image. The experience I gained provides me with an embodied memory, and images will accompany the next part of the story.

The notion of tensegrity reappeared lately during our anatomy sessions, and I realised that most people seemed to have no idea about tensegrity. I had yet to learn that conceptual knowledge has to be embodied for a full understanding.

I had seen a good instruction for building a tensegrity table, and I wanted to give a shot myself. I decided to start with a proof of concept, using PVC instead of copper, trying to translate the imperial measures into metric, adapting a bit for the conversion.

The first prototype didn't work well, the cord length of the main triangles of the tensules was too long. The second prototype taught me about the importance of prestress for the connecting diagonals, and dampened my hope a bit to soon have a nice self-made coffee table.

So I researched the web a bit to stumble across the building instructions for a tensegrity tower made of wooden dowels and plastic cords, and the next visit in the hardware store was due. I don't consider myself a handy man, but I usually don't shy away from manual tasks. Sawing a dowel, drilling some holes and knotting some strings appeared easy preparations to gain some insights to the dynamics of tensegrity structures.

Working on this model allowed me to work on myself as well - I had no time constraints, no boss, no obligation to finish the project, nothing but my curiosity that motivated me. I felt quite proud after cutting the dowel into twelve pieces of similar lengths (2mm tolerance on 20 cm). surprised about the difficulty finding an easy way to drill the holes and about my patience following the instructions step by step. I prepared everything for four tensuls, again translating from imperial to metric measures and improvising with the chocie of materials.

I didn't find stretchy plastic cord, and used nylon string instead. When I tried to assemble the first tensule, the nylon cords wasn't stretchy enough to put the model together. I realised some frustration about preparing more than 30 pieces of string I couldn't use, but decided to make some bigger loops, this time only enough more one model.

I started off with main triangles, and thought about reusing some of the loops already prepared to see how it works out. The first structure that emerged rigid still looked very crooked, I used different length for the connecting diagonals. But I had entered the third dimension, and now wanted to find out a decent length for this 3d puzzle. I unhooked one diagonal, and due to the tension and flopped over from rigid box shape to a messy bunch of rods and strings. Wow.

I found a good length experimentally and prepared the next set of loops for the remaining tensuls. Fixing the orientation of the rods with rubber strings made the assembly easy and fast, and I had four tensuls ready to be piled on top of each other.

The nylon string didn't stretch easily, and I needed some force to threat the first two tensuls together. Although the lower triangle of the upper tensul hung around without tension, the combined tensuls showed increased rigidity.

Finally, I could tune my first tensegrity tower to balance it out. Stunned by the weird thing I build, I took some photos - unfortunately too blurred to be usable. However, as a picture cannot really capture the surprising qualities of a tensegrity model (unless explicitly designed for artistic purpose), I didn't regret capturing this historic moment for me with a crystal clear digital image. The experience I gained provides me with an embodied memory, and images will accompany the next part of the story.

Tuesday, May 5

Elephants and AT

When thinking about animals that move very gracefully, elephants seem not really like typical examples. Outside the circus elephants hardly ever lift more than one foot off the ground, and it looks rather funny when they run.

Do elephants have a place in the Alexander Technique, although they don't move very gracefully? O yes, because positive and negative imagery can influence our thinking. Some people carry thoughts as heavy as a full-grown elephant with them, and just like an elephant these thoughts will stand even taller when they feel threatened.

Depending on the amount and placement of these 'heavy thoughts' the elephants in our mental landscape doesn't stand out, and might even contribute to some sort of heavily loaded balance. As we tend to lean onto our 'heavy thoughts', we hardly notice the elephant in our back, while it might appear highly salient to anyone around us.

Our mental landscape can encompass the entire planet (and even much, much more), yet even in a city-sized mental landscape elephants are hard to find. Unless we feel threatened, engage in emotional warfare, question reality or social rules most of our elephants remain invisible.

Our mental elephants can only survive as long as we feed them. They might not move as graceful as a wild cat, but they move, allowing change. If one of our elephants has died, it still weighs us down, and limits our perspectives.

One way of getting rid of our dead elephant is by eating it. And here comes the Alexander Technique handy. How do you eat an elephant? Ask yourself, and dare a simple answer. Meanwhile I extend this silly picture a bit more. Of course, if our mental elephant in an unvisited part of our mind it might decay before we even learn of its temporary existence.

If we find the dead elephant in a decomposing state, I certainly wouldn't suggest eating it. You might even think it's impossible to do at all. In my humble opinion, the easiest way of eating an elephant is piece by piece. Please don't expect your Alexander teacher serving you elephant steaks (and please believe me that I never have or wanted to eat elephants outside of metaphors).

Learning a skill for life does usually not come easy or fast, I can't eat the elephant at once. And if I forget why I started eating the elephant, I can easily get distracted, bored or frustrated. While we certainly don't learn to move like an elephant, we should invest enough patience not to try to eat an elephant in one piece.

Do elephants have a place in the Alexander Technique, although they don't move very gracefully? O yes, because positive and negative imagery can influence our thinking. Some people carry thoughts as heavy as a full-grown elephant with them, and just like an elephant these thoughts will stand even taller when they feel threatened.

Depending on the amount and placement of these 'heavy thoughts' the elephants in our mental landscape doesn't stand out, and might even contribute to some sort of heavily loaded balance. As we tend to lean onto our 'heavy thoughts', we hardly notice the elephant in our back, while it might appear highly salient to anyone around us.

Our mental landscape can encompass the entire planet (and even much, much more), yet even in a city-sized mental landscape elephants are hard to find. Unless we feel threatened, engage in emotional warfare, question reality or social rules most of our elephants remain invisible.

Our mental elephants can only survive as long as we feed them. They might not move as graceful as a wild cat, but they move, allowing change. If one of our elephants has died, it still weighs us down, and limits our perspectives.

One way of getting rid of our dead elephant is by eating it. And here comes the Alexander Technique handy. How do you eat an elephant? Ask yourself, and dare a simple answer. Meanwhile I extend this silly picture a bit more. Of course, if our mental elephant in an unvisited part of our mind it might decay before we even learn of its temporary existence.

If we find the dead elephant in a decomposing state, I certainly wouldn't suggest eating it. You might even think it's impossible to do at all. In my humble opinion, the easiest way of eating an elephant is piece by piece. Please don't expect your Alexander teacher serving you elephant steaks (and please believe me that I never have or wanted to eat elephants outside of metaphors).

Learning a skill for life does usually not come easy or fast, I can't eat the elephant at once. And if I forget why I started eating the elephant, I can easily get distracted, bored or frustrated. While we certainly don't learn to move like an elephant, we should invest enough patience not to try to eat an elephant in one piece.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)